In this edition

RIP Daniel Kahneman [repost from LinkedIn]

Goal-setting for FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) [Substack-exclusive]

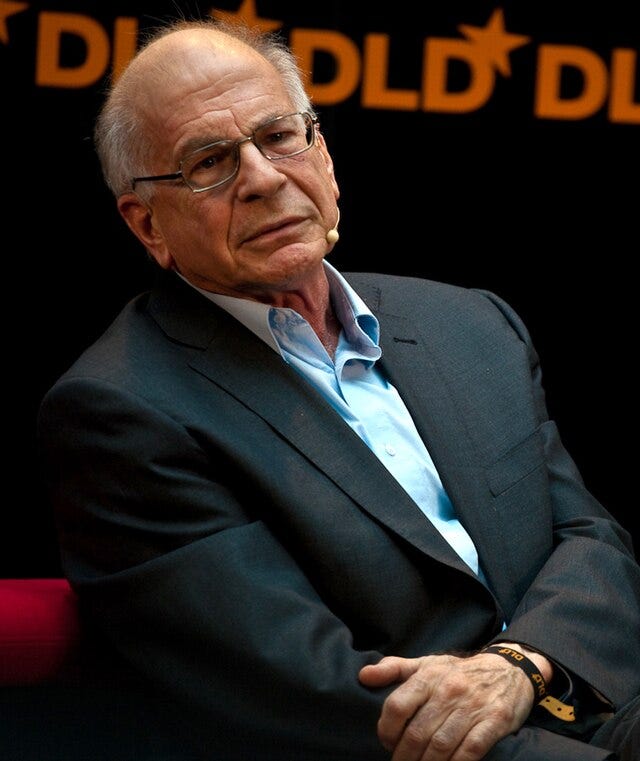

RIP Daniel Kahneman

[repost from LinkedIn]

I’ve been greatly influenced by the work of Daniel Kahneman (who passed away last week, RIP), in particular Thinking Fast and Slow and Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment.

(photo from Wikipedia)

I mostly read non-fiction. 📚 (Curiously, I continue to read management books and articles even though I’m no longer managing or operating.) I particularly enjoy works that explain academic research in an accessible, layperson-friendly way 🤯, especially when it can be applied by the reader.

Kahneman’s writing style is admittedly a bit dry. But when the subject matter — how the human mind works 🧠, in particular the ways in which it is prone to faulty thinking — is so inherently interesting, you don’t need writing flair to find the books incredibly engaging.

The two books showed how biases and noise can affect decision making, and this is how I applied their teachings:

🕵️♂️ Identifying the biases and noise that might distort my own thought processes

🗣️ Identifying the biases and noise in other people’s arguments

🤔 Designing robust decision-making processes that minimise biases and noise

And I may or may not have used these insights to influence a (very) few decisions where I had a really strong preference… 😏

I consider these two books essential reading for anyone who wants to make better decisions (or more precisely, design superior decision-making processes), and strongly recommend them. 🌟

Kahneman was a great thinker, a giant in his field. May he RIP.

Goal-Setting for FIRE

[Substack-exclusive]

Obligatory disclaimer: This is not a sponsored post, and I receive no compensation from this post. This is not investment advice. I may or may not have holdings in any asset or asset classes discussed. Please do your own research and make your own investment and financial decisions.

I’ve mentioned my intent to write about personal finance for accredited investors, and this will be my first post on that, starting with goal-setting. This series of Substack-exclusive posts are not suitable for retail investors, and may not even be suitable for many or most AIs.

Goal-setting is the essential first step, because doing the work to figure out your goal will force you to decide on your desired post-retirement standard of living (which could involve deeper conversations with yourself about your identity), and also ascertain the feasibility of and duration needed for the number you will need (which I’ll just call your “Number”). So I feel compelled to write about this before writing about anything else.

Different people have different motivations underlying their financial goals, and I don’t believe there’s any right or wrong. Some people want to have as much as possible for whatever reason, but I imagine many/most want to achieve financial independence so that they can then freely choose how to spend their time (which could include continuing to work full-time) without the pressure of financial constraints.

And to be transparent, I was incredibly financially irresponsible earlier in my life. I was lucky and privileged enough to have always had well-paying jobs, so I did little proper financial planning or budgeting earlier in my life. In fact I did a line-item breakdown of my expenses for the first time only in June 2020, during Covid, when the end of the world (as we knew it) really seemed possible.

So if you haven’t done any planning or budgeting yet, know that you are almost certainly not alone. Also know that while the best time to start doing it was when you were young, the next best time to start is now.

So what is FIRE? It means “Financial Independence, Retire Early”.

There’s plenty of online literature about this concept (this Investopedia article seems pretty comprehensive), so I’ll only touch on 2 aspects:

How to set your goal.

Understanding — and being honest with yourself — on whether you want to fatFIRE or leanFIRE.

How to set your goal

Many FIRE articles suggest setting the goal as 25x of annual expenses. That’s a rough rule of thumb that seems to have been based on a 1998 study. I’ve not looked into it, but I would personally not make big (potentially 1-way-door) life decisions based on methodologies and data from so long ago, especially since the future decades might look very different from the latter 20th Century.

A better way is to build your own model based on the underlying formula for FIRE. The basic math is quite straightforward:

(Principal) * (Expected rate of annual return) = Pre-tax absolute annual return = (Principal increase to keep pace with inflation) + (Spending money) + Taxes

where

Principal = your Number

Expected rate of annual return = annual investment returns (as a %age) you are confident of generating (gotta be realistic here, over-optimism or over-confidence is just deceiving yourself)

Pre-tax absolute annual return = absolute annual return (in $ terms) from your portfolio

Principal increase to keep pace with inflation = the portion of your absolute annual return that you want to add to your principal, just to keep pace with inflation and preserve purchasing power

Spending money = what you will spend in the year

Taxes = taxes payable on the investment returns

I built a very basic spreadsheet, where you can input your own assumptions in the yellow boxes, and it will spit out the Number required to generate the desired annual spend. (It’s in Google Sheets, just make your own copy to play with.)

A few things about this formula:

This formula adopts an endowment-style approach to retirement funding, where a lump sum of capital (your Number) generates returns to fund expenditures without drawing down the principal. This is different from typical retirement planning for retail investors, which assumes gradual drawdown of the accumulated retirement funds; that is a totally reasonable approach, but it carries longevity risk, i.e. you outlive your retirement savings, which can be mitigated by products like annuities (e.g. CPF Life in Singapore).

The goal is to have the principal generate returns that can be spent or reinvested to keep pace with inflation. So your Number should exclude your primary residence, since it doesn’t generate actual returns that can be spent or reinvested. If you intend to sell your primary residence in future, that is more about how you reach your Number, and will require some assumptions about selling price and also future purchase price (for a cheaper replacement) or rentals.

The formula does not consider lumpy spend, like college education for kids or potential out-of-pocket healthcare costs (which is especially important for those who are currently enjoying generous employer insurance).

The formula does not factor in income during retirement. While the classical conception of retirement implies kicking back on a beach, I suspect many FIRE practitioners will aim for some part-time work or side hustle to generate some income.

When setting the different variables, consider what is your buffer or margin of safety. For example, if inflation is higher than you expected, or actual returns are consistently less than projected, or taxes are increased, then how much buffer do you have to maintain your desired spending level, or would you have to cut back?

There are other important questions, for example around composition of your investment portfolio (i.e. what types of assets you will deploy your Number into), because that determines if you get an income stream or if you have to sell assets to harvest capital gains for income, and also volatility and risk (for example, if your strategy is to sell assets to generate income to spend, you’d have had a very tough 2022). But I won’t get into them here.

fatFIRE vs leanFIRE

Simply put, fatFIRE means retiring early while maintain your current (presumably high) quality of living, while leanFIRE means retiring early with a minimalist and frugal lifestyle. (I won’t get into the other variants like baristaFIRE and CoastFIRE.)

You need to decide what type of post-retirement lifestyle you want. If you are in Singapore, you might have seen a recent article about a 31-year-old man retiring early and living on SGD1k (~USD750) per month, while continuing to live with his parents. That is true leanFIRE, likely with minimal margin of safety (at least so long as he stays in Singapore).

As an avid traveller, I framed it to myself this way: when I travel after I retire, do I want to fly budget, economy, premium economy, or business class? (If you aspire to first class or private, you are not the right audience for my writing!)

You’ve got to be honest with yourself, and you can be truly honest only if you understand your actual current spend at a line-item level (meaning you have itemised pretty much everything you spend on), because that allows you to know what you can eliminate without affecting your current lifestyle. You do also have to anticipate how your spending might change in future, e.g. if you are currently renting but you really want to own your own home.

You also have to know whether your answer is being distorted by your preferred identity. If you like to think of yourself as a frugal person, you might aim to understate your desired spend. That’s completely pointless, because you’re only hurting yourself.

This is a long post about goal-setting, but hopefully it’s helpful, especially for those who have not yet taken these first steps of financial planning and budgeting. Let me know if you found it valuable, and also what areas you’d like to explore! (Again, I won’t write about personal finance for retail investors, especially since there is already plenty of high-quality content serving that segment.)